Why People with Cancer Appear Less Likely to Develop Alzheimer’s Disease?

Posted 1 day ago

4/2026

For decades, clinicians and epidemiologists have observed that individuals with cancer seem less likely to develop Alzheimer's disease than those without cancer. At first glance, this appears paradoxical. Cancer and Alzheimer's occupy opposite ends of biology's spectrum, one characterized by uncontrolled cell growth, the other by relentless cell loss and cognitive decline. Yet, recent research in a mouse model suggests these two conditions might share unexpected common ground.

A study published in the journal Cell provides a molecular explanation for this epidemiological mystery: specific proteins released by cancer cells appear to protect the brain from misfolded protein aggregates characteristic of Alzheimer's disease, a defining pathological feature of the disease. These aggregates, which are clumps of misfolded amyloid-β and tau proteins, disrupt neuronal function and are central to Alzheimer's pathology.

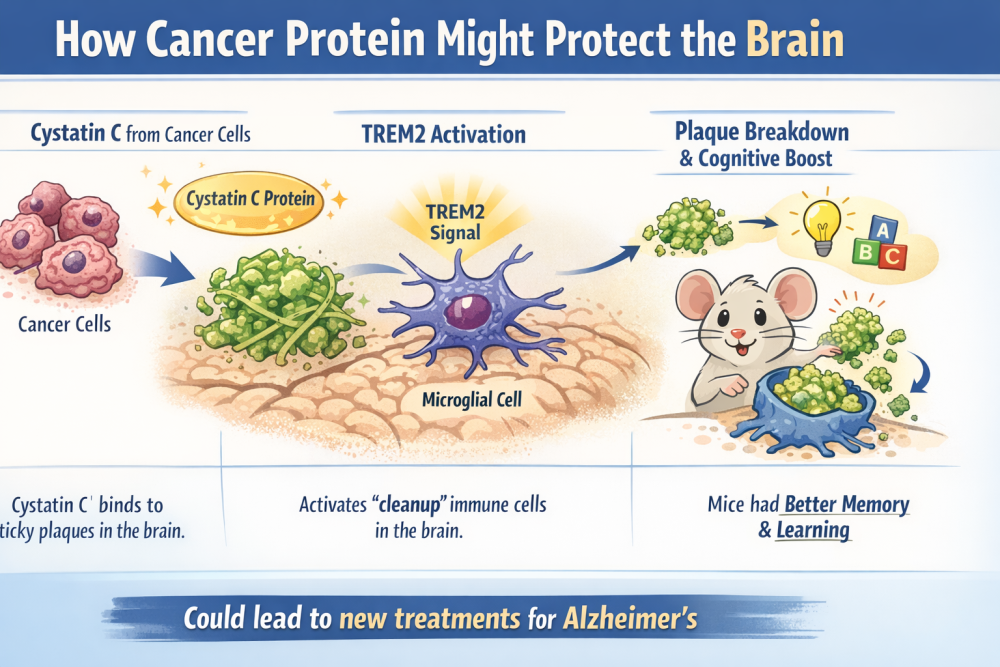

Studies in mice revealed that a protein called Cystatin C can latch onto the sticky substances that form Alzheimer's brain plaques. When this happens, it triggers a helper signal, TREM2 (Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2), in certain immune cells that act like the brain's cleanup crew. Once activated, these cells begin breaking down the harmful plaques.

If future studies confirm the same effect among humans, the discovery could open the door to entirely new treatments for Alzheimer's disease.

Unraveling the Paradox

Cancer's fundamental pathology is cellular proliferation, cells that ignore growth controls and multiply without restraint. Alzheimer's pathology is almost the opposite: brain cells that weaken due to plaque formation, lose connections, and ultimately die. Given these contrasting biological behaviors, why might someone with cancer be less susceptible to neurodegeneration?

Scientists have debated this question for years, mainly because observational data cannot establish cause and effect. Now, controlled studies using mouse models for Alzheimer's disease are beginning to suggest a mechanism. Cancer cells produce and release various molecules into the bloodstream, including proteins that can cross physiological barriers and interact with distant tissues. One such protein appears to enter the brain by crossing through the blood-brain barrier and directly interacts with the misfolded amyloid proteins that accumulate in Alzheimer's disease.

From Tumor to Brain: A Protective Protein

The key discovery from the mouse studies is that a molecule produced by cancer decreases the buildup of Alzheimer's-related protein aggregates in the brain. In Alzheimer's disease, amyloid-β proteins cluster into plaques that interfere with neural communication and trigger inflammation. When the cancer-derived protein reaches the brain, it appears to destabilize these clumps, making them easier for the brain's cleanup systems to eliminate.

While preliminary, these findings offer cautious optimism that molecules from one disease could lead to new therapies for another.

What This Means and What It Doesn't?

It's important to emphasize that no one should conclude that having cancer is "good for the brain". Cancer is a devastating disease with profound effects on health and quality of life. The protective effect observed in mice stems from a specific molecular interaction, not from the presence of the tumor itself.

Although the discovery opens exciting possibilities, developing effective drugs based on this mechanism will take years of rigorous testing and clinical trials. Understanding this timeline helps set realistic expectations and encourages continued interest and support for research into Alzheimer's therapies.

Bridging Two Different Domains of Biological Mechanisms

This line of research highlights a larger theme in modern biology: seemingly unrelated diseases may intersect through shared molecular pathways. By studying how cancer alters systemic biology, researchers may uncover new strategies to bolster the brain's resilience to neurodegeneration.

Of course, significant challenges still exist. Mouse models are valuable research tools, but human brains — especially in aging and diseases, are much more complex. Researchers now need to determine whether the same protective mechanism occurs in humans and, if so, whether it can be safely used to prevent or treat Alzheimer's disease.

Still, these results serve as a reminder that nature often provides answers in unexpected places. A protein once recognized only for its role in cancer biology could someday inspire new methods to protect and preserve the aging brain.

Disclaimer:

The contents provided on www.biomedglobal.org are intended for general informational and educational purposes only. This website's information, articles, and resources are based on data and findings from scientific publications, publicly available research, and reputable sources.

While every effort is made to ensure accuracy and reliability, Biomed Global does not guarantee, endorse, or assume responsibility for the information's completeness, timeliness, or validity.

The material on this website should not be considered a substitute for professional advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Users are strongly encouraged to consult qualified healthcare professionals, researchers, or subject-matter experts before making decisions based on the information presented here.

Under no circumstances shall Biomed Global, its affiliates, contributors, or authors be held liable for any direct, indirect, incidental, or consequential damages arising from the use of, or reliance on, the content of this website.

By accessing and using www.biomedglobal.org you fully acknowledge and agree to this disclaimer.